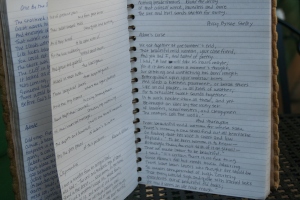

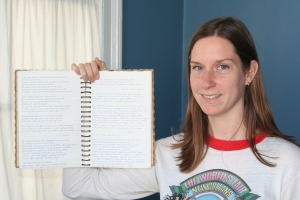

I’m going to cheat here. My book has no name. It looks like this:

I began writing and reading in it in June, 1999. A gift from my high school boyfriend, it is not a journal, but rather a sort of “copy book” as my friend Jay and I have always referred to it. This is a log of loved poems.

I began writing and reading in it in June, 1999. A gift from my high school boyfriend, it is not a journal, but rather a sort of “copy book” as my friend Jay and I have always referred to it. This is a log of loved poems.

I really got serious about it in 2003. Before then, I’d used it for copying snippets of whatever I was reading, mixed with Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, and Velvet Underground lyrics—all the usual stuff for age 17. By 2004, my first year of grad school, I’d filled it up with whole poems copied out mostly by hand. For me, it’s a record of another time, of a sort of naïve faith I had in poems and myself and the world. (I was to win the Yale Younger by 21! Be fluent in many languages and translate for a living! Win a Stegner, a Fulbright, and a Guggenheim! Study at the Academy in Rome! Etc. etc. etc.)

Herein lie the usual  suspects for a young and passionate reader of poems: e.e. cummings, Dickinson. Also a whole lot of Hopkins, Yeats, and Auden. I don’t think I write anything like Hopkins, Yeats, or Auden. But there it is. There they are. Right beside this weird poem by Laura Jensen:

suspects for a young and passionate reader of poems: e.e. cummings, Dickinson. Also a whole lot of Hopkins, Yeats, and Auden. I don’t think I write anything like Hopkins, Yeats, or Auden. But there it is. There they are. Right beside this weird poem by Laura Jensen:

Bad Boats

They are like women because they sway.

They are like men because they swagger.

They are like lions because they are king here.

They walk on the sea. The drifting

logs are good: they are taking their punishment.

But the bad boats are ready to be bad,

to overturn in water, to demolish the swagger

and the sway. They are bad boats

because they cannot wind their own rope

or guide themselves neatly close to the wharf.

In their egomania they are glad

for the burden of the storm the men are shirking

when they go for their coffee and yawn.

They are bad boats and they hate their anchors.

…..

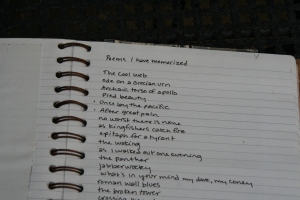

I love this book because when I am completely fed up with poetry and feel certain it will never again speak to me, a poem in here will. When all modes seem tired and there are too many books, poets are assholes, teaching is misguided, and art is self-indulgent and useless, I can flip through this book, reluctantly, and some phrase will jump out: “Beyond all this, the wish to be alone” (Larkin); “In a dark time, the eye begins to see” (Roethke); “so many languages have fallen” (Clifton). Poems I used to know by heart, or nearly. Lines imprinted on some neurological path of mine and, certainly, in the minds of others.

This book influences my writing because these poems have a life in my brain. Have clarified my life, my brain. Probably the rhythms of the language more than anything else—what I’ve taken in subconsciously, what I’ve relied on to remember them.

This book influences my writing because these poems have a life in my brain. Have clarified my life, my brain. Probably the rhythms of the language more than anything else—what I’ve taken in subconsciously, what I’ve relied on to remember them.

I think it was Linda Bierds, in a workshop at the University of Washington in 2001 or 2, who turned me on, in her sweet wisdom, to this idea. I don’t think it’s an amazingly original one, though I do wonder how many poets my age (I’m 30) are copying their favorite poems out by hand these days.

I don’t do this anymore. Now I keep a separate notebook in which I write about every book I read—quotes, whole poems, thoughts, publication data. It doesn’t serve the same purpose or have the same effect as this one does. It’s more orderly, formal. Driven less by urgency and more by habit. Like an adult.

And I don’t love all these poems anymore, either. I’m not, after all, such a huge fan of Anthony Hecht or Denise Levertov or Randall Jarrell. But, re-reading what’s here, I remember what I loved, or learned. They clarify what I want or do not want, what I value. I still love “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner,” anyway.

Also, this book is not politically correct. Women and minorities are grossly under- and mis-represented. Many of the poets have been dead for a hundred years. And that’s just the point. When I read these poems and let myself be moved, I can let go of my own expectations, criteria, and notions of what it’s acceptable to love, what it’s all right to like. What a gift, to be divested of those.

Rescue Press published Melissa Dickey’s first book of poems, The Lily Will, in October, 2011. She lives, teaches, writes, makes stuff, and mothers in New Orleans, LA, with her husband Andy and their two small children.

Rescue Press published Melissa Dickey’s first book of poems, The Lily Will, in October, 2011. She lives, teaches, writes, makes stuff, and mothers in New Orleans, LA, with her husband Andy and their two small children.

A friend lent me her copy of The Lily Will. Loved it’s fresh and sharp images. Insightful, economical and beautiful. Congratulations!

We are so happy you enjoyed Melissa’s collection! It is such a stunning book! Thanks for your support.

Pingback: Safety Book #21 (Blueberry Morninsnow) + Black Box Poetry Prize Info: | RescuePress